Why this article?

Introduction to Disability Studies (in Art History).

Terrific examples of Ekphrasis.

Art as evidence.

Path to the present that connects our brief studies of Surrealism, Feminism, Queer Theory in Art History, Intersectionality and Disability Studies in Art History.

As I lead a close reading of the first 6 pages,

|

| Frida Kahlo, Remembrance of an Open Wound, 1938 |

In Remembrance of an Open Wound (1938), Mexican artist Frida Kahlo painted herself seated in a chair against a barren landscape, staring with an unyielding and unashamed returned gaze at the viewer and lifting her Tehuana-Mexican dress to display her bare legs. Her left leg, which caused the artist pain and impairments throughout her life due to childhood polio and an accident on a Mexico City bus at the age of eighteen, is wounded by leafy thorns and spurts blood onto her dress. Her left foot, which was amputated at the end of her life in the 1950s, is pictured bandaged and also bleeding. Roots that sprout from Kahlo’s body and connect it to nature, a crown of flowers and thorns on her head, and the thorny site of her seemingly self-inflicted scars evoke imagery of Aztec sacrifice and healing rituals, as well as Christian martyrdom, influences characteristic of Kahlo’s oeuvres. The title of the painting appears on a flowing ribbon within the composition, reminiscent of Mexican retablos,

|

| Retablo Painting |

devotional images of creolized Mexican-Indian/ Catholic saints performing healing rituals that were painted on wood panels and were quite popular in modern Mexican religious and vernacular culture. Themes of self- scarring and martyrdom in this work have been related to Kahlo’s biography and disabilities, the many infidelities of her husband (Mexican muralist and painter Diego Rivera), and specifically a recent sexual affair between Rivera with Kahlo’s sister, Cristina Kahlo. Lifting the elaborate native Indian dress she was known for wearing, in this painting Kahlo reveals her wounds, and yet, a strictly biographical reading of these wounds veils their potent symbolism within the multireferential composition.

|

| Frida Kahlo, Two Fridas, 1939 |

Surpassing reference to one specific event, Kahlo’s wounds are psychic, sexual, and corporeal, as her wounded and painted body is marked by her personal and cultural history. The dress itself represents intersections between cultural signs and Kahlo’s individual style and has been a detail misunderstood, in my opinion, by many viewers who make assumptions about her body as broken, wounded, and degenerate due to her disabilities. Kahlo’s main biographer, Hayden Herrera, and many others have suggested that Kahlo wore such dresses to “hide” her limp and the scars from her accident and many surgeries, ignoring the period trend among the intellectual elite to wear such costume as a symbol of Mexican Nationalism. Further, as depicted in this painting, the dress serves as an instrument of revealing and concealing and Kahlo’s mediation of her disabilities for the public. She raises her skirt to reveal the wounds, placed strategically and erotically on the upper thigh, yet she holds the hem down over the space at the center of the canvas to which the viewer’s eyes are drawn—between her parted legs. In her painted self-image, Kahlo performatively covers and simultaneously flaunts her sex with manipulation of the dress. The dress frames and showcases the wounds she purposively displays for the viewer, as her brightly colored, elaborately patterned and ornamental costumes in real life would have attracted additional attention to her body. These dresses become a means for ornamentation and glorification of the body, and a means for the wearer, or performer, to self-direct the stares her body received in everyday life, due to her limp and other impairments.

Remembrance of an Open Wound is one of over a hundred self-portraits, many executed from Kahlo’s bed during times of convalescence with an elaborately staged easel and overhead mirror. These self-portraits often display Kahlo’s personal and medical body histories in images of her numerous miscarriages, surgeries, recoveries, and physical degeneration. The “self” portrayed in Kahlo’s work emerges as a body in pieces—graphically ripped apart, wounded, bleeding, and impaled. Other works in her oeuvres document her friends, family, Native Indian, German, and Spanish-Mexican heritages, medical experiences, personal tragedies, daily domestic life in early twentieth-century Mexico, and her international travels. Each work is a carefully choreographed, symbolically and visually dense, not to mention colorful composition, rather than a one-dimensional depiction of her “suffering,” a characteristic reading of Kahlo’s paintings that has overshadowed their rich significances. Kahlo’s paintings serve as public performances of identity whose significances and legacy exceed the frames of her disabled body, as well as the frames of her historical context.

Kahlo’s work falls before the contemporary time period that is the focus of this book, but her influence looms large in contemporary artworks, as well as in my analyses of them. Kahlo was ahead of her time in her unashamed, graphic, and performative bodily displays of disability. Many more recent artists have drawn inspiration and vivid imagery from Kahlo’s compositions, for a range of reasons.

|

| Carmen Lomas Garza, Lotería-Tabla Llena, 1972, hand-colored etching and aquatint on paper, image: 13 7⁄8 x 17 5⁄8 in. (35.3 x 44.9 cm) sheet: 16 3⁄4 x 21 in. (42.5 x 53.3 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, 1995.50.59, © 1972, Carmen Lomas Garza |

|

| Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas, 1944 |

|

| Lavinia Fontana, Antonia Gonsalus, 1595 |

|

| Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Portrait of Sebastián de Morra (c. 1645), oil on canvas, The Prado Museum, Madrid. |

Diego Velazquez, Las Meninas, 1656

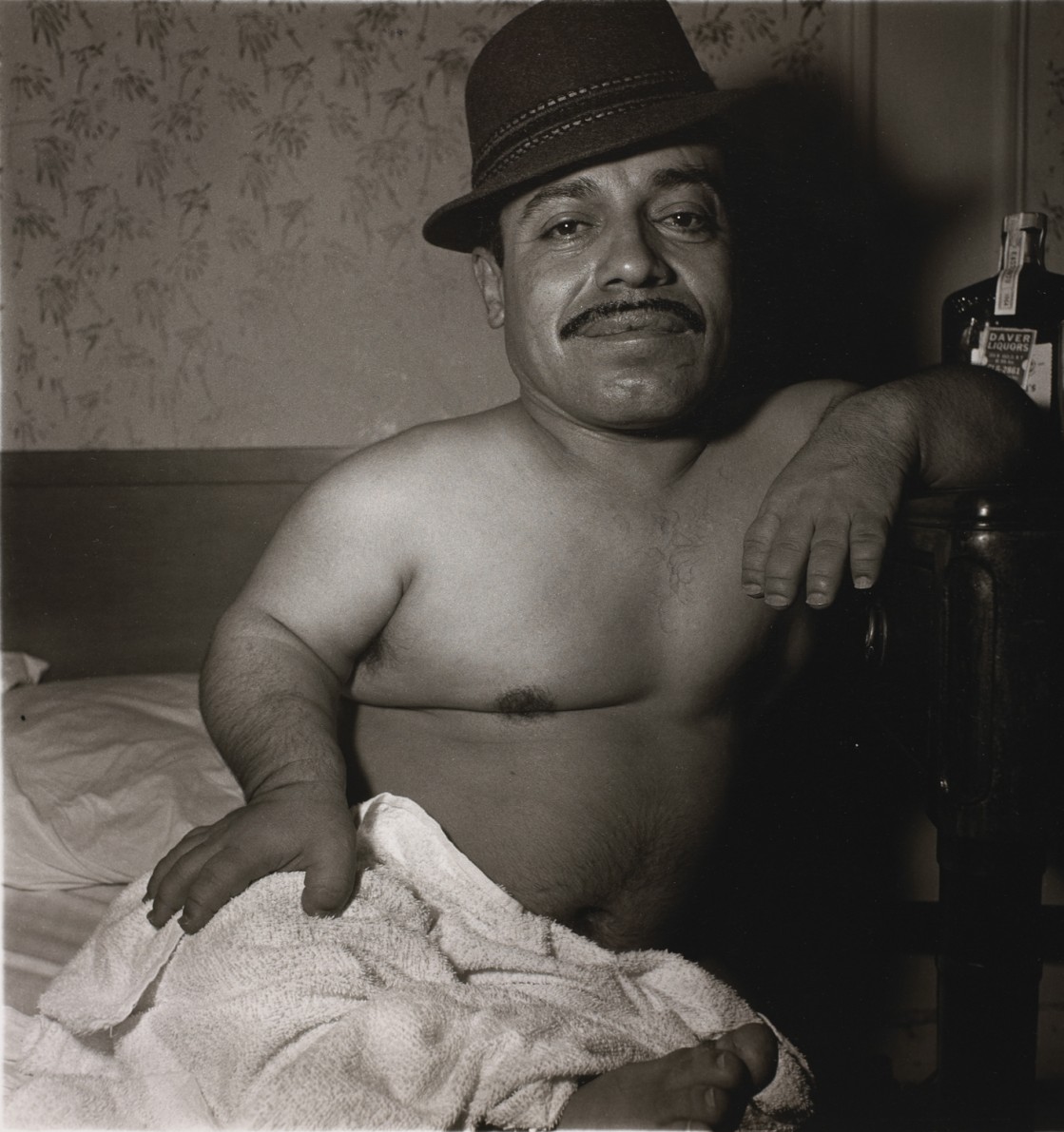

Diane Arbus, Mexican Dwarf in His Hotel Room, gelatin silver print, 1970

|

| Diane Abrbus- Russian midget friends in a living room on 100th Street, N.Y.C., 1963 |

|

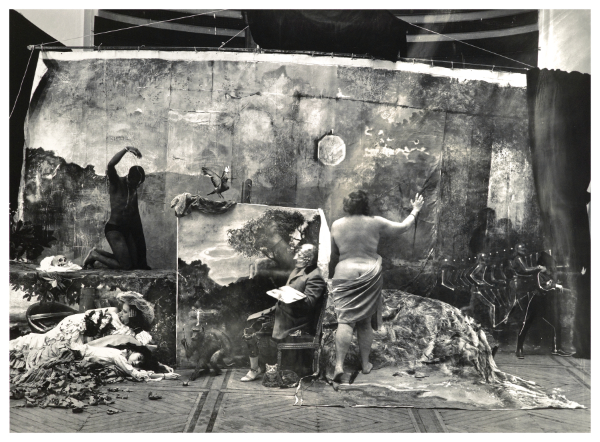

| Joel-Peter Witkin, Studio of the Painter Courbet, 1990. Courtesy the artist. |

|

| Joel Peter Witkin, Las Meninas (Self Portrait After Velasquez, 1987 |

|

| Marc Quinn, Alison Lapper, 2007 Fourth Plinth |

|

| Marc Quinn, Alison Lapper, 2007 |

Friday, March 1

In-class: Body, Performance, and Making Mary Duffy, Orlan,Judith Scott Bufano, Matthew Barney and Amy Mullins

Comments

Post a Comment